A Production Production©1998–2025 Dustin Putman

|

|

Don't trust the cynics and pessimists who claim movies aren't as good as they once were (depending on the age of the person opining such a thing, this could refer to any decade between the 1920s and the early days of the 2000s). Sure, 2016 had its share of unnecessary remakes, distaff sequels, and overpriced misfires (what year doesn't?), but the amount of greatness on display—films of creative innovation, thematic complexity, emotional authenticity, and superlative performances—far outweighed the more rotten offerings.  The key to locating these special motion pictures that aren't afraid to take chances while tackling a bevy of compelling subject matter is in one's ability and willingness to search outside of the Hollywood mainstream. Independent cinema, foreign films, documentaries, and the work of true auteurs were in full force this year, and, yes, there were even a handful of stunners from the major studio system, too.

Out of the 180+ films I saw in 2016 (the full running list can be found here), at least 25 of them could have easily made it onto my Top 10 list. In a lesser year, they would have. This year, alas, there were a lot of sacrifices to be made, with the understood compromise that the rest of them would be included in my "honorable mentions" section.

The format of this year-end essay remains the same. I begin with highlighting the best performances I saw over the 12-month period, followed by my choices for the most underrated picture of 2016, and (new this year) the most overlooked film of this calendar year. There are never, ever a dearth of outstanding movie moments, and I have chosen 10 of my favorites. Finally, my personal lists for the 10 worst and best films I saw in 2016 will be revealed. Hopefully there will be something (or a lot) here for everyone. If you feel as if film isn't what it used to be, look harder. Chances are, you'll be pleasantly surprised with what you find.

(my pick for the absolute best is indicated in red)

Best Actor

Best Actress

Best Supporting Actor

Best Supporting Actress

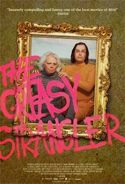

"The Greasy Strangler," "The Greasy Strangler," written and directed by Jim Hosking, is an acquired taste with a mighty limited audience, but for those who are drawn to and admire the weird, the nauseating and the unstoppably absurdist, this just might be the 21st century's cult film to end all cult films. Of all the movies I screened in January at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, this was, by far, the most endlessly surprising. Hosking and co-scribe Toby Harvard prove to be masters of the ridiculous, frying up a one-of-a-kind cinematic experience so insanely unique it's kind of fantastic. Part B-movie spoof, part gory slasherama, the film shocks, appalls, and will leave a quadrant of the audience in outright stitches. Once you see "The Greasy Strangler," you will never, ever be able to unsee it. For the strong of stomach and adventurous lovers of the original and bizarre, this graphically gonzo, oddly heartfelt father-son saga is a gift from the midnight-movie heavens. Its limited theatrical release was brief, exiting screens seemingly as quickly as it arrived. Just wait, though; its moment of well-earned discovery is coming.

"The Sea of Trees," "The Sea of Trees," directed by Gus Van Sant, is a head-scratcher not for the film itself, but for the baffling, near-universal venom it inspired from the critical community following its premiere in May at the Cannes Film Festival. Based on this vicious reaction and the picture's current 12% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, one would expect an outright disaster, a grievous dramatic miscalculation that has gone wrong in unimaginably profound ways. Instead, the deeply poignant, lushly poetic "The Sea of Trees" is a singularly rewarding experience, treating its characters and central locale—Japan's Aokigahara, nicknamed "Suicide Forest"—with equal parts esteem and empathy. In telling the story of a man in crisis (Matthew McConaughey) unable to reconcile the tragic circumstances the universe has dealt him, Van Sant and screenwriter Chris Sparling have crafted a picture both sensitive and melancholic, emotionally raw yet ultimately inspiring. In one of the most vivid supporting turns of the year, Naomi Watts is close to astonishing as wife Joan, a functioning alcoholic who, in just a handful of exquisitely adept moments, is able to build a world of history with McConaughey, the sting of life's most bitter and unfair turns giving them perspective on what is, ultimately, most important.

(In alphabetical order; please note this section contains plot-centric spoilers)

The single funniest scene of the year may be in Ben Falcone's "The Boss," as shamed former titan of industry Michelle Darnell's (Melissa McCarthy) dinner at a five-star restaurant takes a turn for the worse when she opts to enjoy a risky, paralyzing pufferfish dish. This set-piece is so perfectly written, performed and edited for maximum comic impact it scarcely would matter even if the rest of the film fell flat (it doesn't).

Having narrowly survived a nightmarish dinner party hosted by savage cult members, Will (Logan Marshall-Green) and Kira (Emayatzy Corinealdi) gaze out across the rolling Hollywood Hills, the darkened landscape illuminated by portentous red lanterns and the rising scream of sirens, in Karyn Kusama's "The Invitation." In an instant, they must face the terrifying realization their ordeal was not merely a self-contained event.

Weary over attending her umpteenth failed audition, aspiring actress Mia Dolan (Emma Stone) lays it all on the line with show-stopping eleventh-hour ballad "Audition (The Fools Who Dream)," in Damien Chazelle's lovely musical "La La Land."

Long estranged following a shared personal tragedy, former husband and wife Lee (Casey Affleck) and Randi (Michelle Williams) have a wrenching chance encounter, discovering their grief may be too insurmountable to forge a new friendship, in Kenneth Lonergan's "Manchester by the Sea."

In Barry Jenkins' deeply felt "Moonlight," a now-grown Chiron (Trevante Rhodes) visits the roadside diner where Kevin (André Holland), the former classmate with whom he shared his first homosexual experience, works. They haven't seen each other in at least a decade, but, as Barbara Lewis' "Hello Stranger" plays dreamily on the jukebox, their reunion immediately stirs up the personal bond they shared all those years ago.

In Tom Ford's emotionally ravaging "Nocturnal Animals," disillusioned Los Angeles gallery owner Susan Morrow (Amy Adams) comes to the gradual, devastating conclusion her ex-husband (Jake Gyllenhaal) has not only stood her up for dinner, but never planned to meet her in the first place. Guilty of a betrayal she cannot take back, Susan will now have to lie in the bed she's made for herself. Only trouble is, she's an insomniac.

Entering the final days of a brave fight with terminal cancer, mother-of-three Joanne (Molly Shannon) speaks candidly to grown son David (Jesse Plemons) about the mistakes she's made and regrets she has, in the process providing them both some much-needed solace, in Chris Kelly's remarkable "Other People."

15-year-old Conor (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo) imagines the ideal music video for his irresistibly rousing new pop song "Drive It Like You Stole It," in John Carney's "Sing Street."

A little past the midway point of Mike Mills' poignantly observed "20th Century Women," the film's voiceover narration suddenly unshackles itself from the 1979 present when single mom Dorothea (Annette Bening) matter-of-factly and without warning reveals she will be dead from lung cancer in twenty years' time.

An investigation into a missing otter slows to a hysterical crawl when rabbit investigator Judy Hopps (voiced by Ginnifer Goodwin) and wily fox Nick Wilde (Jason Bateman) pay a visit to a very, very, verrrrrry slow sloth at the Department of Motor Vehicles, in Byron Howard and Rich Moore's dazzling, incisive, computer-animated "Zootopia."

| Suicide Squad

It might be a tad harsh to call "Suicide Squad" an outright disaster, but it comes far too close for comfort to earning this misbegotten label. A lumbering, tone-deaf, barely coherent adaptation of the D.C. Comics series by John Ostrander, the picture takes a seemingly can't-miss concept—one pitting bad guys looking for redemption and/or freedom against genuine evil forces—and then squanders it to criminal degrees. Despite being written and directed by David Ayer, the film carries a messy made-by-committee vibe, one that has no idea what it is doing or how to do it. The characters (with the exception of Margot Robbie's Harley Quinn) couldn't be any flatter or blander. The candy-colored opening studio logos and end credits bookend a grungy, dreary, stylistically destitute visual scheme, full of boring backlot locations and desperately unimaginative action scenes. For two hours, "Suicide Squad" flops around, gasping for focus, purpose and interest. In short, it's a tacky mess. |

|

| Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows

2014's Michael Bay-produced "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" was undemanding popcorn silliness. For all its leaps in logic (and what else would a person expect from a fantasy-adventure starring four 6-ft.-tall heroes in half shells named after Italian Renaissance painters?), the film capably told its story with pleasing portions of involving action fireworks and heart. In contrast, "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows" is soulless tripe, director Dave Green (who showed such promise with 2014's "Earth to Echo") concocting an unctuously busy follow-up that never takes a breather long enough to concern itself with the people—human or reptile—involved. As is often the case with sequels, a very clear attempt has been made to go bigger and more bombastic, with increasingly wearisome results. The narrative is choppy nonsense, with characters hopping around with little regard to basic elementary coherence. Action set-pieces are uninspired and familiar, with all the urgency of a stroll to the mailbox. In a cast where none of the actors have anything of note to do, it is Laura Linney whose beyond-awkward appearance is most worthy of discussion. Playing Rebecca Vincent, the all-business captain of the Bureau of Organized Crime, Linney clearly cannot believe she has found her way into a movie called "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows." No matter what she is saying, her eyes seem to be pleading for help. Even when she finally smiles at the end and offers congratulations to the heroes, it is done through gritted teeth. Her disdain for this project is not only plainly obvious, but, as it turns out, wholly warranted. |

|

| Martyrs

Pascal Laugier's 2008 French-Canadian film, "Martyrs," is a cinematic watermark, one of the twenty-first century's defining works of the horror genre. Unblinkingly brutal, psychologically terrifying, and ultimately unshakable in its thematic search for no less than the existence of God, the picture is not for the easily shaken, yet rewarding for those who stick with it. This English-speaking redux takes its predecessor's basic blueprint, but cushions its edges, clunkily relies on exposition to spell out its plot, and truncates the story's timeline to such a degree it only serves to make its final scenes all the more preposterous. Mark L. Smith, who also wrote 2015's extraordinary "The Revenant," might want to consider burying this credit on his resumé, while directors Kevin Goetz and Michael Goetz bring nothing fresh or special to their achingly inferior version. Indeed, just about every alteration made to this retelling is the wrong one. "Martyrs" is soft and calculated and really rather dumb, not a fraction as effective as its source material. Whatever purpose this film has for existing is indecipherable. |

|

| Demolition

When his wife is killed in a car accident, a curiously unfeeling businessman (Jake Gyllenhaal) busies himself in the lives of a customer service rep (Naomi Watts) and her moody teenage son (Judah Lewis) while taking a literal sledgehammer to his beautiful home. Director Jean-Marc Vallèe hit consistently authentic notes with his previous acclaimed features, 2013's "Dallas Buyers Club" and 2014's "Wild," but he can barely find a single one that rings true in "Demolition." Set in what is intended to be a facsimile of the real world, this hokey dramedy is ceaselessly contrived to the point of surrealism. Emotions are forced and overblown. Characters strike as insufferable stick figures rather than actual people. The screenplay by Bryan Sipe is too cute and quirky and two-dimensional by a half, ultimately leading nowhere of plausible consequence. Attempts at metaphors club viewers over the head with clumsy transparency. Considering—and in spite of—the talent involved, "Demolition" is strikingly misguided. It would be so twee it hurts if it weren't equally spiteful and disingenuous. |

|

| Mother's Day

It is depressing to consider that this offensively trite all-star holiday comedy will be the final entry on late director Garry Marshall's filmography. Best to instead remember the legend for his career highlights ("Overboard," "Beaches" and "Pretty Woman," among them). Choppy, haphazardly manipulative and shamelessly pandering, "Mother's Day" sputters along from story to story and flimsy character construct to flimsy character construct with no apparent sense of pacing, grasp of the passage of time, or awareness of its own zero brain-celled insipidness. Almost entirely bereft of charm or credibility, the film is so out of touch it might as well take place on a faraway planet where the inhabitants look human and have names, but are otherwise blank robotic slates. The funniest moment in "Mother's Day" arrives during its end-credits blooper reel. Julia Roberts, sporting a ginger-helmeted fright wig, sits in a café, staring forlornly into the distance as a seemingly never-ending locomotive barrels past the window. Finally she breaks. "That's one really fucking long train!" she exclaims. Roberts' honest, off-the-cuff reaction is startling precisely because the film preceding it has been such a wasteland of painful, prefabricated inauthenticity. Gifting this movie to one's own mother for the holiday should be reserved for those holding a diabolical grudge against her. |

|

| God's Not Dead 2

When soul-searching student Brooke (Hayley Orrantia) asks a question in class comparing Gandhi to Christ, 11th-grade AP history teacher Grace Wesley (Melissa Joan Hart) gives what she believes is a succinct, straightforward answer, citing a passage from the Bible to back up her affirmative response. This solitary moment sparks outrage among secular parents and the public school board, sending Grace, who maintains she has done nothing wrong and refuses to apologize, directly to court. The core debate swirling around the characters in faith-based drama "God's Not Dead 2" is not an invalid one, but the nuance and complexity of the issue is traded in for ludicrous, over-the-top grandstanding and the kind of insipid stereotyping that reveals it to be nothing more than a hypocritical charade. Director Harold Cronk and screenwriters Chuck Konzelman and Cary Solomon tackle this project with the authenticity of third-graders who have no idea how the world works or even that the spectrum of human emotions and religious belief can be shaded beyond inky blacks and snowy whites. Alas, any thoughtful questions the film poses are thrown out in favor of an ignorant ulterior motive to represent Christians as oppressed martyrs whose magnitude of discrimination goes far beyond that of other forms, be it racism or xenophobia. Religious persecution is a serious matter, but "God's Not Dead 2" hasn't a clue how to approach it without condescending to its target audience and casting a spurious, uniformed shadow over anyone else on the screen who doesn't happen to share the same spiritual beliefs. Under the guise of well-meaning moralizing, the picture little by little reveals an ugly and distasteful hidden agenda, one that self-righteously goes against the movie's alleged messages of acceptance and religious freedom. |

|

| Sharkansas Women's Prison Massacre

The best thing about "Sharkansas Women's Prison Massacre" is its ludicrous title. It's all downhill from there. An abysmal entry in the killer-animal subgenre, this chintzy, low-rent farce features XXX-level acting and production values but not a stitch of nudity for the viewers' troubles. The movie must know it is bad, but is frequently so earnest it is difficult to tell. Squarely aiming for an audience of straight males who see nothing wrong with bro culture, veteran D-grade exploitation filmmaker Jim Wynorski casts an ensemble of slim, pouty, big-breasted women ready-made for a Hustler spread as a group of female prisoners on work detail in the Arkansas bayou besieged by prehistoric, dirt-swimming sharks. Headlining this embarrassing affair is the once-promising Dominique Swain, whose most notable catchphrase, "Crap on a cracker!" is repeated four times because three simply wouldn't do. From one moment to the next, the movie cannot be bothered to make the barest modicum of sense, but it cheerfully plows forward for 83 blessedly short minutes without an IQ point in its empty, little head. Alexandre Aja's "Piranha"—or even Sy-Fy's "Sharknado"—this is not. |

|

| The Brothers Grimsby

When a movie's highlight is a thoroughly repulsive scene where two men hiding inside an elephant's vagina become trapped there as the animal is gang-banged, it is pretty telling evidence the project is a bit of a disaster. In a far, far, far cry from Sacha Baron Cohen's provocative, hysterically pointed past satires—2006's "Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan," 2009's "Bruno," and 2012's "The Dictator"—"The Brothers Grimsby" is a lead-footed spy comedy so disinterested in its story, characters, comic timing and middling emotional trajectory it feels less like a completed film and more like a vague but gratingly unpleasant fever dream. Directed by Louis Letterier, the film is bereft of anything to think about or anyone to care about, a crass assault lacking perspective, purpose, or even a semblance of heart. Even at less than 80 minutes sans end credits, "The Brothers Grimsby" is about as pleasurable as elephant semen to the face. |

|

| Dirty Grandpa

Robert De Niro and Zac Efron hit the nadir of their careers with "Dirty Grandpa," a movie so annoying, so ugly, so lead-footed, so misguided, and so blisteringly unfunny it has to be seen to be believed. Please don't see it, though. There is a fine line between ribald and unremittingly obnoxious, and this tone-deaf, hostile, endlessly insufferable "comedy" crosses it in the first scene and stays there for an unbelievable 108 minutes. In a race to humiliate every actor involved, director Dan Mazer (2013's likable revisionist romantic comedy "I Give It a Year") and writer John Phillips have created a conveyor belt of caricaturized human monstrosities for them to portray. Toss in insults directed at gay characters and the offensive use of a disabled person whose disability is meant to be the pinnacle of hilarity, and what we have is an absolutely disgraceful assault on its genre. "Dirty Grandpa" is painful, charmless and cruel, carrying a bleak outlook on humanity legitimately alarming to behold. Even viewed as nothing more than a frivolous trifle, it is stomach-churning in its contempt for audiences. |

|

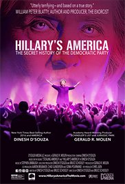

| Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party

"How will you know when you've become an American?" author-director Dinesh D'Souza asks near the end of "Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party." "You'll know when you've become a Republican." Disgustingly exclusionary following 106 minutes of radical far-right delusions, this closing note is at the dismayingly inflammatory heart of the film's very message. Less a documentary than an extended episode of Comedy Central's "Drunk History" as told by a zombified Fox News Channel commentator, this pitifully acted, reenactment-heavy propaganda piece finds a way to lay the blame on 21st-century Democrats for every single negative thing that has ever occurred in U.S. history. For political free-thinkers who have even a cursory understanding of the past and the complexity and nuance of the country's progressivism, the film can be viewed as nothing more than laughably incendiary hogwash. It isn't just a roundelay of blatantly naive falsehoods, hideous misinformation, and fictional imaginings, however, but also serves as plainly inept filmmaking, full of mind-numbing reenactments that make dinner theater look like comparative beacons of historical accuracy. Meanwhile, D'Souza positions himself as the main attraction, a creepy conspiracy theorist who loves to hear the sound of his own voice. He likens himself to a truth-seeking messiah of the people, but spends nearly two hours preaching divisiveness. "Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party" earns unintentional laughs time and again, but at a certain point it stops being funny and becomes offensive instead, frightening in its constitutional debasement and exploitative sideshow spectacle. It couldn't be any more un-American if it tried. |

|

| La La Land

A movie musical not based on existing source material is rarer than it might seem in 2016, viewed by most major studios as a costly gamble not worth taking. Director Damien Chazelle has not only defied the odds with "La La Land," but has hit a swirlingly incandescent high note. Giddily ambitious but perhaps more bittersweet than some will be expecting, this melodic love story proves fanciful but rooted, emotionally, in a reality where happily ever afters are not certainties. As Hollywood-based dreamers Mia and Sebastian, played with heart-on-sleeve grace by Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling, navigate the excitement of a new relationship, it is only a matter of time before the messiness of real life gets in the way. Chazelle and his actors make every success and pitfall dramatically involving and honest, backed by a lovely soundtrack of original tunes composed and orchestrated by Justin Hurwitz. With unmistakable shades of Jacques Demy's "The Umbrellas of Cherbourg" and "The Young Girls of Rochefort" written into its DNA, "La La Land" imagines a reality where singing and dancing is as natural as breathing. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren proves unencumbered by the rules of conventional lensing, his camera swooping, gliding and even taking flight while observing the characters (who, in one scene set at Griffith Observatory, also defy gravity). Is Mia and Sebastian's a forever kind of love? Director Damien Chazelle does not sugarcoat the truth of his story, using the gift of song as a dramatic expression far more resounding than the spoken word possibly could. |

|

| Swiss Army Man

"Swiss Army Man" is a beautiful conundrum, an outlandish but achingly honest rumination on what it means to emotionally live and what it means to physiologically pass on. There is plenty to be discussed of Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert's unusually innovative feature writing-directing debut, but one point is undeniable: with just a single film under their belt, they have blazed a trail all their own. Telling the one-of-a-kind story of an island castaway (Paul Dano) who finds unexpected hope—and a friend—when a corpse (Daniel Radcliffe) washes ashore, Kwan and Scheinert's veritable tightrope walk could have easily turned into an embarrassing wipeout, spoken about for years to come as simply bad, bad, bad. Fortunately, it is neither bad nor a wipeout, taking bold risks and paying off in profound, vital spades. To merely describe the pop-infused existentialism of this delirious, thoughtful gem is to not properly do it justice. "Swiss Army Man" is a work to experience and lavish over in all its gloriously eccentric singularity. |

|

| Hello, My Name Is Doris

There are well-written film and television characters, and then there are those who are conceived with such vibrant, irresistible specificity they almost cease being merely fictional personalities on the screen. This is most definitely the case with Doris Miller, the irrepressible heroine of "Hello, My Name Is Doris." In what is the best movie role she has taken on in at least two decades, Sally Field is flawless as Doris, a meek sixty-something office worker still grieving the recent loss of her mother who decides to finally start living for herself. As writer and director, Michael Showalter (who previously penned 2014's romantic spoof "They Came Together" and 2001's cult summer-camp satire "Wet Hot American Summer") exhibits a detectable newfound growth and maturity with this lovely, aching, frequently hilarious human study. Where the picture leads and how it gets there is both expected and yet not, favoring emotional honesty over banal adherences to convention. The film is tonally adept, knowing when to spring for humor and when a restrained touch is necessary. Capturing the truth of each situation, however, is Showalter's reigning priority, and he remains steadfast in seeing Doris through her arrested coming of age. Indeed, it is her cumulative growth as a person more than her desired romance with much younger co-worker John (Max Greenfield) that means the most by the end, though this latter question—sustained clear through to the pitch-perfect final scene—only adds to one's involvement in her journey. Like its blessedly quirky, heart-on-her-sleeve title character, "Hello, My Name Is Doris" is beautiful and irreplaceable just as it is. |

|

| Christine

The troubled times and tragic end of Sarasota news journalist Christine Chubbuck is gifted a piercingly empathetic cinematic account in the haunting, miraculous "Christine." Rebecca Hall delivers the performance of her still-young career, a transformative turn that seemingly channels the late reporter and finds the earnest, frustrated, tortured soul within her. For two absorbing hours, Hall's title heroine has seemingly been given uncanny new life and, in a roundabout way, another chance to be heard. Those familiar with the infamous true story of Chubbuck will nonetheless hope some way, somehow her fate will change for the better. Much of the credit must go to director Antonio Campos and screenwriter Craig Shilowich for giving this forlorn figure so many different layers and shades. Yes, she is destined to take her own life, but she is not defined by this. Instead, the film sees her as a young woman with ambition to spare but awkward social skills, someone who longs to do meaningful work and is left discouraged when others are all too willing to sacrifice their morals for the bottom line. When the film reaches its shattering conclusion, one finally feels as if he or she understands who she was, what she believed, and why she ultimately decided to publicly take her own life on July 15, 1974. "Christine" aches with compassion and humanity for its real-life subject. |

|

| Sing Street

There are no two ways about it: "Sing Street" is pure bliss. Writer-director John Carney's 1980s-set musical ode to growing up and finding one's passion takes place in a cynical world, yet has no time or patience for cynicism. Uplifted on the winds of great storytelling and an impeccable understanding of the popular music of its era, the film is a tad grittier—at least visually—than John Hughes' classic teen pictures, but very much at one with their bittersweet, ultimately hopeful tone and empathetic depictions of adolescence. "Sing Street" is sweepingly romantic, not only in regard to possibly star-crossed teens Conor and Raphina (played in breakthrough performances by Ferdia Walsh-Peelo and Lucy Boynton), but concerning the melodies which form the soundtrack of their coming of age. This is the kind of joyous movie where audiences drift out of the theater as if on a cloud. |

|

| Hush

"Hush" makes it look so easy. A masterclass in suspense, "what-would-you-do?" terror, and intimate, razor-sharp female empowerment, the film takes a straightforward, albeit exceedingly shrewd, premise—a young deaf women is stalked at her remote country home by a sociopathic intruder—and wrings it for all it's worth. In whittling down the narrative to its taut essentials, writer-director Mike Flanagan has crafted a filmmaker's calling card guided by the pure elements of cinema. His thrilling mise en scène—all achieved, it should be noted, with minimal dialogue and a mute lead protagonist portrayed in a smashing performance from co-writer Kate Siegel—dares not miss a beat as the already sky-high stakes raise ever more. Beautiful in its narrative simplicity, observant in its human complexity, and vital in its stylistic precision, this is the kind of nerve-shredding thriller which lays waste to its viewers' fingernails while leaving said audience literally perched on the edge of their seats. So tense and involving as to make everyone watching a flinching, wincing, cheering participant, "Hush" ought to join the best works of Alfred Hitchcock, John Carpenter and Brian De Palma as a future teaching tool in genre film courses. This is how it's done. |

|

| The Invitation

A distressing knockout of pin-prick precision and harrowing consequence, "The Invitation" is a film that will not—and cannot—be forgotten. Masterfully actualizing a stunner of a script written by Phil Hay and Matt Manfredi, director Karyn Kusama establishes herself as a legitimate filmmaking force, someone who can take a single location and create from this a tour de force of emotionally aching transcendence and nearly unbearable slow-boiling dread and tension. "The Invitation" takes its time yet wastes nary a frame, each moment methodically, sublimely building as a get-together with friends and loved ones treks toward a creeping pall of peril. At its center is Will (Logan Marshall-Green), returning to the idyllic Hollywood Hills home where he no longer resides but memories both irreplaceable and unthinkable still exist. Is he being paranoid of his hosts' intentions, or does he have a right to be worried? A nerve-shredding climax, capped by a final shot as brilliantly alarming as it is hair-raisingly evocative, seals the deal on a picture dripping in dark, rapturous portent. Part of the stressful pleasure of watching "The Invitation" is in guessing where the story is headed and, once discovered, recollecting on where it has been. This isn't a horror-thriller-as-magic-trick, though. Quite the contrary, it is a splendidly ominous, beautifully constructed exploration into damaged peoples' lives and the awful, fallible turns they can take. |

|

| Arrival

There is a fine yet tangible line between great films and true, test-of-time masterpieces, and "Arrival" (based on Ted Chiang's short story "Story of Your Life") crosses this threshold very early on and somehow gets even better from there. Transcending genre classification even as it stands as one of the finest cinematic achievements in modern science-fiction storytelling, director Denis Villeneuve's (2015's "Sicario") latest stunner threatens, at times, to become too overwhelming. Striking but unforced, rousingly operatic in its achingly resplendent grandeur and intimacy, this is a picture to savor, to be humbled by, to fall in love with, and to be in absolute awe over. In one of the best performances of the year, Amy Adams is incredible as linguisitics professor Dr. Louise Banks, accepting the daunting yet untradeable task of communicating with an extraterrestrial species that has come to Earth. Exquisitely structured in surprising ways which only gradually reveal themselves, "Arrival" proves thoroughly mesmerizing. Conventional action is kept to a minimum, yet 2016 has scarcely seen such an exciting film. A plethora of subjects—ruminations on our existence, on our drive for connection, on the sacrifices we make, on our yearning to love and be loved no matter the stakes—ensure there is always just as much to think about as there is to be dazzled by. Furthermore, it earns every one of its tough emotional beats, the sheer beauty and reverence within frequently enough to catch in one's throat and bring a tear to the eye. At the film's center is Louise, tasked with learning who these interplanetary beings are and why they're here, and instead finding a common ground and unspoken unity that goes far beyond language. "Arrival" is one for the ages. |

|

| Nocturnal Animals

It has been a long seven-year wait for fashion-designer-turned-filmmaker Tom Ford to return behind the camera—his last picture, 2009's "A Single Man," was a stirring, stylish debut—but it is very clear from the formidably bravura results he was not merely resting on his laurels. An American mosaic charred in disillusionment and regret, "Nocturnal Animals" (based on the 1993 novel "Tony and Susan" by Austin Wright) is mysterious, disturbing, and altogether devastating. It's also not quite like anything that has come before it, unfolding in multiple timelines and varying states of reality as an unhappy gallery owner (Amy Adams, shattering) begins to grapple with her empty life and the reckless decisions she's made after receiving the manuscript of her ex-husband's (Jake Gyllenhaal) harrowing debut novel. "Nocturnal Animals" deepens in menacing, mournful and miraculous ways the further it proceeds and the longer one ponders it in hindsight. Every last image captured by cinematographer Seamus McGarvey's lens is beyond sumptuous, frame-worthy snapshots in delicate, evocative motion. Unshakable as much for what isn't said as for what is, the picture hauntingly burrows its way into one's inner recesses, electrifying nerve endings and plaguing the heart. To be sure, David Lynch and the late, great Robert Altman would be exceptionally proud, but Ford's complex corkscrew of shifting narratives and parallel subtexts is very much its own organism—playfully experimental in form, endlessly provocative in content, and visually ravishing to behold. "Nocturnal Animals" is bold and breathtaking, a profound human tragedy with a devil's wink. In a word, it's extraordinary. |

|

| Other People

In a year overflowing in greatness, no motion picture rang quite as true or moved me quite as profoundly as writer-director Chris Kelly's magnificent debut feature. "Other People" is beautiful in every way, an incisively funny drama accomplishing the Herculean task of eliciting comfort even as it breaks one's heart. The story of a terminally ill mother (Molly Shannon) and the grown gay son (Jesse Plemons) who comes home to assist his family in caring for her may sound like the setup for a maudlin Hallmark Channel movie, but Kelly finds such unblinking intimacy and honesty in his every moment it never becomes anything other than its own lovely, singular entity. The first film in memory to leave me teary-eyed 30 seconds in and laughing by the one-minute mark, the film earns catharses through its accuracy, forthrightness and empathy of tough subject matter. Jesse Plemons and Molly Shannon are revelations through and through as David and Joanne, the former never fully accepted by his father and wanting to know he still has a place to come home to when his mom is gone, and the latter struggling to tie up loose ends and hold onto her dignity even as her body starts to shut down. "Other People" works sublimely in tandem as a character study, a familial slice-of-life, and a mother-son love story. The recurring use of Train's 2001 rock ballad "Drops of Jupiter," initially as a running gag and then, ultimately, as an emblem of loss, resiliency and life itself, proves transcendent. "Other People" is one of the most deeply touching films to come around in quite some time—maybe ever. |

|

|

© 2016 by Dustin Putman

|

|

|

|